Welcome to this week’s Research Roundup. These Friday posts aim to inform our readers about the many stories that relate to animal research each week. Do you have an animal research story we should include in next week’s Research Roundup? You can send it to us via our Facebook page or through the contact form on the website.

- Alcohol and Magnesium Chloride shown to be effective anesthetics for cephalopods. Researchers at San Francisco State University found that both alcohol and magnesium chloride prevented the brains of cuttlefish and two species of octopus from perceiving negative stimuli (being pinched). The aim was to discover whether these compounds were true anesthetics, or whether they just prevented physical responsiveness in the animals (without preventing pain). The Magnesium Chloride took longer to act, leaving the animal paralyzed, but still feeling for the first 15 minutes, whereas the ethanol shut down movement and sensation much faster. Published in Frontiers in Physiology.

- Genetically altered antibodies protect rhesus monkeys from HIV-Like Virus. On April 16, scientists from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) reported that two genetically modified broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) protected rhesus macaques from an HIV-like virus. Single infusions of each bNAb protected two groups of six monkeys each against weekly exposure to simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) for over half a year. The team from NIAID demonstrated that the genetic mutations in the bNAbs increased their durability following injection, and extended the period of protection, but did not affect the way the antibodies bound to the virus. If proven safe and effective in humans, this extended activity in the body could potentially allow for longer periods between clinical visits to receive the treatment. Published in Nature Medicine.

- Biomedical tattoo gives early cancer warning. Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a biomedical tattoo that can detect four common types of cancer from elevated levels of calcium in the blood, which warns patients by growing an artificial mole on their skin. This technology was tested in mice and samples of pig skin with much success, but must be reactivated annually. The biomedical tattoo uses calcium detecting cells to signal the production of melanin when blood calcium levels are high. The melanin darkens the skin to form a mole at the site of the tattoo. The rise in calcium, termed hypercalcemia, is associated with forms of prostate, lung, colon, and breast cancer. Further research will adapt the system to monitor neurodegenerative diseases and hormonal disorders. Published in Science Translational Medicine.

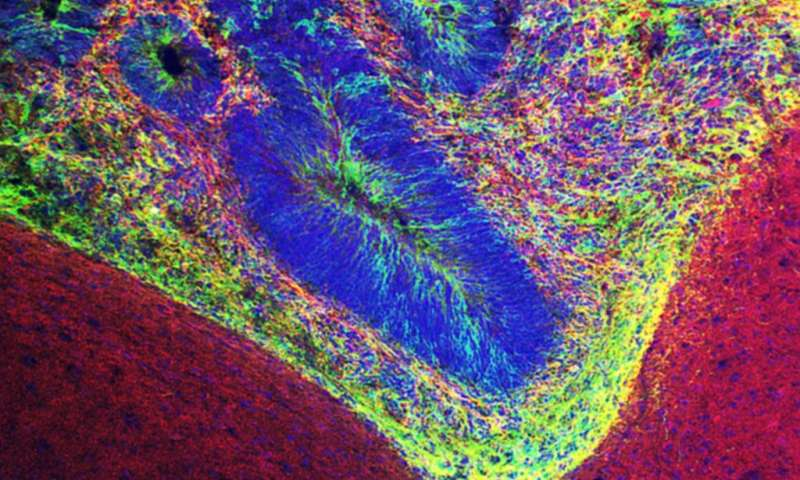

- Miniature human brains implanted in mice. The first publication describing the implantation of lentil-sized human cerebral organoids into mice suggest this technology will be used to understand human brain development, may serve as repair kits for stroke, and repair injured or underdeveloped areas of the brain. Scientists at the Salk Institute in California took human brain organoids that had been growing in lab dishes for 31-50 days and then implanted them in over 200 mice. Around 80% of the organoids implanted successfully and began sprouting new neurons within 2-12 weeks. The mice showed no demonstrable cognitive difference to common mice. We previously discussed this research when it was announced in November 2017 at the annual meeting for the Society of Neuroscience.Published in Nature Biotechnology.

- Inhibiting a protein to prevent heart failure. Researchers at the Cincinnati Children’s Heart Institute, have piloted an experimental molecular therapy, called pUR4 in heart cells damaged by a heart attack. This therapy, which blocks a matrix-forming protein, called fibronectin, reduced levels of scarred muscle tissue and in a mouse model prevented heart failure. This work is important because reducing levels of scarring permits for retention of function, which otherwise, would lead to further complications. Published in the journal Circulation.