Why do we need to use animals in experiments?

Aren’t animals different from people?

What is the difference between animal research and animal testing?

Don’t we have alternatives to animal research?

Is all research on cats, dogs and primates?

How do researchers decide which species of animals to use for an experiment?

Don’t the animals suffer in experiments?

Who cares for animals’ welfare in labs?

What happens to animals after the experiment?

Is animal research morally justifiable?

If your question relates to claims made by animal rights activists you may wish to check out our “AR pseudoscience” page.

Why do we need to use animals in experiments?

There is still a lot we don’t understand, both about how our body functions and how it can be affected by disease. If we want to develop future treatments for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, cancer, or heart disease, then we need to understand the causes of those diseases, how they spread, what they do to our body, and how we could stop those processes. We can learn a lot from studying people, just as we can understand a lot from looking at cells – healthy and unhealthy – in petri dishes, but all of these methods have advantages and disadvantages. Many studies require a full living organism in a situation where it would be unethical, or impractical to use humans. For example, understanding the progression of breast cancer might involve giving a healthy animal a tumor, similarly understanding the genes which contribute to breast cancer might involve breeding genetically modified mice to see what changes occur when genes are added or removed.

The history of medicine is a catalogue of treatments made possible by the careful use of animals in experiments. This includes everything from the development of blood transfusions in the early twentieth century, to the HPV vaccine developed in the early twenty-first century. It is not just the testing of these treatments, but the use of animals in developing the scientific knowledge that underpins these advances.

Studying other animals is also an important way to learn about them. Studies in the behavioral sciences, including comparative psychology, animal behaviour, zoology, and ethology, have all produced discoveries about animals’ behaviour, learning, memory, cognition, and other processes. In turn, this scientific knowledge provides a foundation for many advances that benefit humans and other animals. For example, it has allowed us to better understand how the brain works to produce and affect behaviour and how that is similar and different across species. At the same time, knowledge about other animals informs advances in care and understanding of those animals in both wild and captive settings.

Aren’t animals different from people?

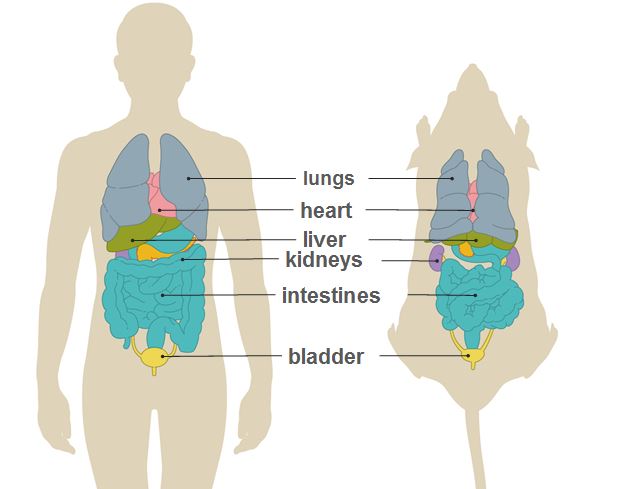

Humans and other animals are more similar than one might think. Our biological similarities allow for human conditions to be modeled in animals. However, choosing an animal model can be challenging for scientists since there are some genetic and physiological differences between species, just as people differ from one another. Moreover, animal models of human diseases are only as good as our understanding of that human disease at a given time. Since science is an evolving process, each animal model of a condition furthers our basic biological understanding and may contribute to future therapeutic advancements. Importantly, those future therapeutic advances may not be obvious when the basic research that ultimately underpins it is undertaken.

What is the difference between animal research and animal testing?

Animal research is an umbrella term for the vast array of scientific research that goes on – ranging from studying animal behaviour in the wild to understanding disease in an animal in the lab. The types of research that occurs in labs are similarly varied, including modelling disease, understanding physiology and genetics, the development of human and veterinary treatments and more. One specific area of animal research is “animal testing”, which aims to assess the safety and efficacy of potential new drugs (human and veterinary) and chemicals. These tests tend to be necessary for regulatory approval, before a drug can move through to future safety stages (such as human testing), and tend to come after the compound has been shown to be safe in non-animal tests. So while all “animal testing” is a form of animal research, not all animal research is “animal testing”.

Read more in our article, “Animal research is not ‘animal testing’“.

Don’t we have alternatives to animal research?

The Animal Welfare Regulations require scientists to “reduce, refine and replace” (The 3Rs) the use of animals in research, and this is done to the extent that is possible. In every university or research institution in Europe and North America there is some form of review panel that must approve new research projects, ensuring they adhere to the 3Rs principle. In the US, this review panel is known as the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee that supervises every research project and makes sure that it complies with this requirement. Nevertheless, completely eliminating animal research without compromising the whole biomedical research enterprise is not currently possible. Russell and Burch, who developed the 3Rs framework, wrote:

“Desirable as replacement is, it would be a mistake to put all our humanitarian eggs in this basket alone. The progress of replacement is gradual, nor is it ever likely to absorb the whole of experimental biology.”

Computer modeling, micro-dosing, MRI scanning and in vitro testing are often touted as alternatives to the use of live animals. However, it is highly doubtful that they will ever completely replace the use of animals in research. The reason for this is that every scientific method is designed to answer a particular type of question, so that methods that use animals, cell cultures, computer models or imaging of the human body, complement rather than replace each other. For example, computer modelling can only be done if we already have information to put in the model. There is no way of acquiring this information other than going into a living organism to look for it. In vitro experiments, which are done with molecules (like proteins or DNA) or cell cultures, are very good to unravel mechanisms that happen inside the cell, but are not always so useful to find out, for example, how different cells, tissues and organs interact inside the body. For the foreseeable future, we will need to use live animals to answer some of the most important scientific questions related to human health. Further, research aimed at producing new knowledge about the behaviour, biology, brain, and other systems and processes in other animals will always depend on studies of those animals.

Is all research on cats, dogs and primates?

No. Mice, rats, birds and fish account for 95% of all research animals in most countries. Less than 1% of research studies involve cats, dogs and primates.

How do researchers decide which species of animal to use for an experiment?

The species of animal that is selected for a particular biomedical experiment is determined by the specific goals of the experiment, the knowledge we have about that animal species and how it compares to the condition in humans we are modeling. For example, the pig is a model that is commonly used to study how heart attacks (myocardial infarction) occur and how they can be treated because the blood vessels that supply the heart in pigs is very much like that in humans. In contrast, if congestive heart failure is being studied, the dog is a better model than the pig because the muscle wall of a dog’s heart responds to conditions that lead to heart failure similarly to humans. There is no one animal model that simulates everything that occurs in humans and scientists must show why their selected species is a suitable model for their research.

For research aimed at producing new knowledge about the behaviour, biology, brain, and other systems and processes in other animals the choice of which animal to study is driven by the research question. Better understanding the cognitive capacities of fish will depend on studying fish, for example. In comparative research, new discoveries are made through studying both similarities and differences between species. For instance, differences in the brain—or nervous system—of mammals, fish, and birds can inform our understanding of evolution, development, environmental effects and brain mechanisms involved in different kinds of behavior.

Don’t the animals suffer in experiments?

Researchers, veterinarians and animal care staff make every effort to minimise unnecessary pain and suffering within labs. Many of the procedures carried out on animals involve minimal pain or discomfort. For instance, animals’ behaviour may be observed, or tissue samples may be collected after the animal is humanely euthanized. Nonetheless, some procedures will involve pain or discomfort when the nature of the experiment makes it unavoidable. In some cases, the study of, and the evaluation of therapies for, painful medical conditions such as severe infection or injury may have the potential to result in significant levels of pain and discomfort. In these cases efforts will be made to alleviate pain, for example by using anesthesia and analgesia during and after surgery, though just as with human patients it is not always possible to alleviate pain completely. In the UK in 2015 just 4.5% of animal research procedures were classified as ‘severe’, meaning a major departure from the animal’s usual state of health and well-being. However, the level of pain and discomfort is kept to as low an intensity and short a duration as possible. Before an experiment can take place, a Risk-Benefit (America) or Harm-Benefit (Europe) Analysis must be conducted. This critically weighs up the potential medical or scientific benefit against the potential pain or suffering of the animal. The study will be given a severity level (expected level of pain or suffering for the animal) which cannot be exceeded, and if necessary humane endpoints (the point at which an animal must be euthanized to prevent any future pain or suffering) will be included in the license.

Not only do scientists work to design studies that minimize pain, suffering or distress to research animals, but there are strict regulations in place to ensure that animals in research do not suffer unnecessarily. In fact, animal research is the most heavily regulated activity involving the use of animals. In the US, all procedures must be approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee(IACUC) to ensure that they follow laws and regulations like the Animal Welfare Act and Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Animals. The IACUC carefully examines how every animal is going to be used, paying close attention to the pain and stress involved in all procedures. Of course, suffering is not limited to pain and stress; an animal can suffer when its biological or social needs are not met. All animals are cared for by animal care staff, researchers and specialized veterinarians that supervise the animals’ health and well-being. Besides providing the animals with food, water and a clean, comfortable living environment; care is taken to enrich the lives of animals through species-appropriate enrichment – this could be thicker bedding for nesting species or objects to climb to certain animals etc. Social animals (like rats) must be housed in groups unless doing so can be shown to jeopardize the scientific objectives or the animals’ health and safety. In summary, researchers do everything possible to minimise any suffering on the part of the animals they use in research, and where suffering is unavoidable they take every possible measure to reduce that suffering to an absolute minimum.

Who cares for animals’ welfare in labs?

Everyone involved with animals in labs has a responsibility to care about their welfare. There are numerous professional groups that are actively involved in the welfare of laboratory animals. There are also scientists and specialty fields of research that conduct studies to identify the best practices to house and care for animals. Animal care technicians, specialized veterinarians and scientists are all dedicated to the welfare of the animals in their care. These animals are treated with compassion and respect by the professionals that care for their daily physical and psychological needs.

The use of animals is highly regulated with numerous national, regional and local laws, regulations, policies and guidelines set in place to ensure the oversight of studies. The animals’ welfare is of extreme importance to the highly trained professionals caring for these animals and it is their duty to report any concerns.

Replacement, reduction and refinement guide the ethical use of animals in science. Scientific objectives must be balanced with consideration of animal welfare. Research plans must replace or avoid the use of animals where they would have otherwise been used, employ strategies that will reduce the number of animals used and continuously refine and modify experimental and husbandry procedures to minimize pain and/or distress.

What happens to animals after the experiment?

While some animals may be used again, or sometimes even adopted out, most animals are humanely euthanized. This is usually because certain information, such as organ samples, can only be taken after the animal is euthanized and the body subjected to further analysis. This information is just as important as measurements taken during the life of the animal.

While there are many efforts to allow suitable animals (dogs, cats etc) to be adopted where possible (where a post-mortem examination is not needed), many species are not appropriate to keep as pets. Even traditional pet animals, such as dogs and cats, can have different needs as a result of living in a laboratory. These animals are used to being surrounded by fellow animals, as well as receiving attention from people throughout the day. As a result, they may not be suited to life as a house pet (particularly if an only pet, or where it will be left alone in daytime). Further to this, there are around 1.5 million unwanted dogs and cats euthanized in animal shelters in the US every year, and adding to this number may not benefit those already looking for a home.

Is animal research morally justifiable?

The belief as to whether animal research is ethical is individual to each person. At the heart of it we are making a judgement as to whether humans are more important than animals – do we have a right to kill an animal to save a human, or indeed do we have a duty to do so? Our individual answers can have big implications – should one person’s belief that animal research is unethical prevent another person from using the medical treatments made possible by such research? Furthermore, since much biomedical research directly, or indirectly, contributes to improving animal health (e.g. veterinary medicine or environmental research), it is not only humans who have a stake in this question.

The regulatory framework in most countries demands that animal research may only take place where the benefits of scientific research outweigh the harms to animals, and where there are no viable alternatives to the use of animals. Under these stringent conditions, most Governments and scientists around the world believe it is moral and necessary to conduct research on animals in carefully regulated circumstances.