On November 17, 2015, the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) sponsored a congressional briefing highlighting the role that canines play in advancing both human and dog health. Attended by Congressional staffers and other stakeholder, the briefing highlighted three panelists who described how studying naturally occurring diseases in dogs improves our understanding of corresponding human diseases.

Timothy Nichols, MD, Director of the Francis Owen Blood Research Laboratory at UNC-Chapel Hill opened the briefing by discussing his research on hemophilia, a rare blood disorder where sufferers lack clotting factors and have uncontrollable bleeding. Some dogs, like humans, are genetically prone to hemophilia and have been instrumental in learning more about the disease and in identifying new treatments of hemophilia for dogs and humans. Many of the therapies available to humans have been developed in susceptible dog breeds, and more therapies are currently being tested. For example, Dr. Nichols explained that dogs treated with gene therapy have been disease free for over seven years. He hopes that this treatment can soon be applied to humans.

Following Dr. Nichols was Amy LeBlanc, DVM, DACVIM, Director of the National Cancer Institute’s Comparative Oncology Program. Dr. LeBlanc oversees clinical trials where pet dogs with naturally occurring cancers are enrolled in studies through the Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium to test new treatment paradigms. Results from treating dog patients are used to help inform trials with analogous human cancers. Dr. LeBlanc noted that dogs are a great model for studying cancer relevant to humans because dogs are outbred, exposed to the same environment and stresses, and have genetic profiles similar to humans. Additionally, dogs are immune-competent and cancer metastasis occurs in a comparable manner to humans.

Elaine Ostrander, PhD, Chief of the Cancer Genetics Branch at the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health, discussed her research studying the canine genome. Using DNA samples of pure-bred dogs supplied by pet owners, breeders, and veterinarians, Ostrander’s laboratory identifies the genetic basis for specific traits. For example, studying the genetic profile of dogs with short legs (e.g., corgis, dachshunds) led to the understanding that a specific gene is responsible for an excess of a specific growth factor resulting in an inhibition of cartilage forming cells, slowed bone growth, and shortened legs. Identifying of this gene may help researchers address growth conditions in humans.

During the question and answer period, the panelists were asked a number of questions by audience members. The importance of using the correct animal model for the scientific question being asked was highlighted and emphasized by Dr. Nichols’ response, “hemophiliac mice don’t bleed, dogs do.” When the panelists questioned whether animal models of disease were becoming more important in studying human disease, there was an emphatic “absolutely” by all speakers.

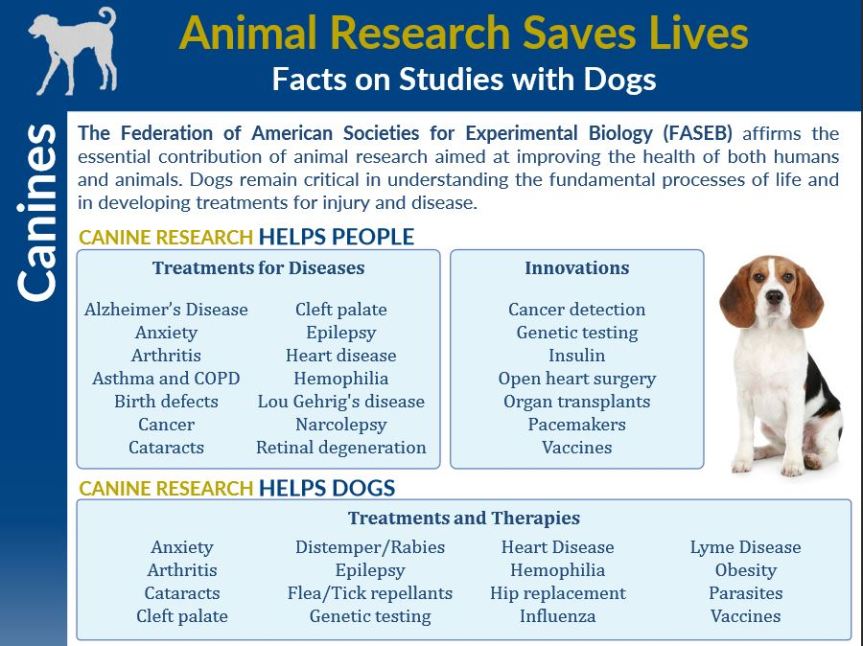

To coincide with the briefing, the Federation also released a new canine research factsheet (partially pictured above) detailing the ways in which research with dogs has improved human and canine health and the many ways in which it is regulated. The factsheet and other educational materials were distributed to attendees—including congressional staffers—and can be found on FASEB’s website.

Often, congressional offices hear about animal research only from those who are against it. These briefings allow for researchers to speak directly to the staff of influential lawmakers and explain the importance of animal models in biomedical and biological research. These types of outreach events are crucial in helping to dispel the myths perpetuated by those opposed to animal research.

Speaking of Research