This open letter is from scientists and leaders in the addiction research community. If you’d like to join the signatories listed below, please do in comments at the bottom of this article. Please also share with others with an interest in research on addiction.

Smoking – and nicotine addiction – are sometimes easy targets for criticism by many people. For others, addiction is a mental health issue of deep concern, affecting one in seven Americans during their lifetime, often resulting in immeasurable suffering and even death. There are many reasons that addiction can be an easy target and perennial candidate for ridicule. One is that some believe addiction is “simply a matter of weak willpower,” evidence of a “moral failing,” or some other character flaw. In this, we see parallels to medieval beliefs that schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression were due to witchcraft, demonic possession, wandering uteruses, and weak moral character.

Addiction is a brain disorder

Through decades of scientific study of the brain, behavior, genetics, and physiology, we now know that addiction is a complex disorder affected by neural function, genes, and the environment. We also know – at a specific level – about the brain chemistry and circuits that increase the risk for and play a role in addiction—including smoking. Unfortunately, there is still a lot we do not know, including questions such as: Why are some individuals vulnerable to addiction and others not? Why does relapse after any kind of treatment occur at such phenomenally high rates? Why do drug abusers persist in seeking and taking substances that so clearly will lead to incarceration, poverty, even death?

It is these gaps in knowledge – along with empathy for those suffering because of addiction—that lead the nation’s health research agencies to actively support addiction research. Yet, there are others who seek to end this lifesaving research. For example, a months-long campaign by the anti-animal research advocacy group White Coat Waste Project targeting nicotine addiction research recently got a boost from Jane Goodall, the celebrity primatologist known for research on chimpanzee behavior. This marks yet another high profile pairing of Goodall and groups fundamentally opposed to all nonhuman animal research. Here, Goodall wrote to the head of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about research on nicotine addiction in monkeys conducted at the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR).

Addiction costs the US billions each year

What Goodall claims is that the research is a misuse of taxpayer’s money because of her belief that ‘the results of smoking are well-known in humans’, and that the same research can be done in humans. Both statements are shocking, no less so because they come from a prominent scientist whose very profession is based on reporting facts.

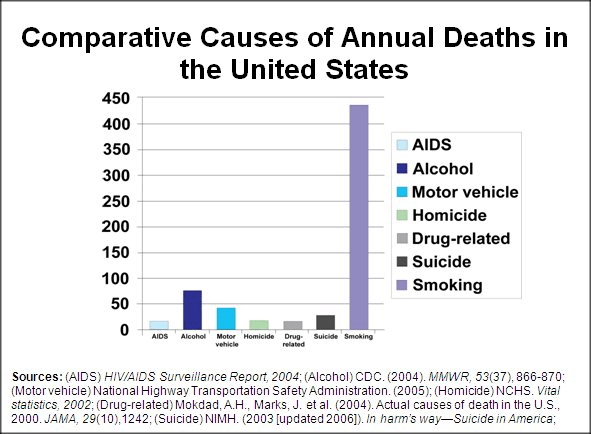

Even a cursory glance at the state of tobacco use in the US gives some clues as to why statements like this are irresponsible: According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), tobacco use kills approximately 440,000 Americans each year. Given the White Coat Waste Project’s interest in saving the taxpayer’s money, the estimated economic impact of tobacco use, including everything from healthcare costs to cigarette-related fires, is almost $200 billion per year (see NIDA Research Report Series online, 2012). So, clearly nicotine addiction remains a significant public health problem and it is quite evident that we do not understand this disorder well enough to eradicate it—current treatments basically have just slowed it down. There is much work to do.

Outright wrong: the FDA nicotine research Goodall targets is not taxpayer funded

There is another blatant inaccuracy in Goodall’s letter to the FDA, namely, the very idea that this is a fraudulent waste of taxpayer’s money. In fact, the funding source for NCTR nicotine research is the Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), which was established to oversee implementation of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009.

What is important here is that CTP funding comes from “tobacco user fees” charged to manufacturers of tobacco products. In other words, no taxpayer’s money is funding this research. How can the public trust any claim by Goodall and White Coat Waste if even this basic fact was ignored?

Why research with humans cannot answer the full range of questions

What is lost in the simple formulation that Goodall uses is the fact that research with humans cannot answer fundamentally important questions that are basic to progress in understanding, preventing, and treating addiction. Species other than humans take drugs. The fact that monkeys and rodents “self-administer” drugs in a manner similar to humans provides scientists with an extremely valuable model of drug addiction. The discovery of the “reward center” in the brain, the role of the chemical dopamine, even the basic principles of many behavioral therapies for addiction—all of these basic findings come from studies with monkeys and/or rodents self-administering drugs. In fact, the discovery that nicotine is the primary ingredient of tobacco products that contributes to their addictive properties, as well as the designation of nicotine as a drug of abuse, relied on self-administration studies. And yet, we are just at the beginning of understanding addiction as a brain disorder (rather than a simple moral failure or a series of bad decisions).

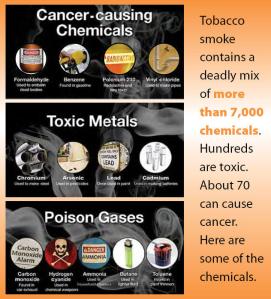

Instead of using monkeys in nicotine addiction research, Goodall suggests that ‘smoking habits’ can be studied ‘directly’ in humans. These two scenarios are entirely different—you don’t study ‘smoking habits’ in monkeys (who generally don’t go to the local gas station for some smokes). Smoking habits are an incredibly important part of nicotine addiction, but studying nicotine self-administration has entirely different goals. For example, the NCTR researchers are interested in brain changes following nicotine taking in adults and adolescents. What the monkey experiments allow them to do is isolate just nicotine (burning tobacco creates approximately 7000 chemicals)

and study its effects in a highly controlled environment. This approach allows the researchers to draw much firmer conclusions about effects on brain function than could ever be obtained in people smoking cigarettes. To treat nicotine addiction, we have to know precisely what nicotine does to the brain, and we need to do this in a systematic, carefully controlled manner. We also need to know, however, what all the other chemicals are doing in order to understand the “real life” situation. Studying nicotine alone provides a platform for going about doing those types of studies, eventually recreating the real life experiences of the tobacco abuser.

Absolutism is different from consideration of animal welfare

Research in laboratories with animals is conducted humanely, ethically, and under careful oversight guided by federal and state laws, regulations, guidelines, and by institutional policy. Importantly, it is unclear what evidence Goodall and White Coat Waste have for any serious violations of regulations at the FDA facility. It may be the case that Jane Goodall and White Coat Waste are opposed to animal research that is conducted in order to benefit human health. That is a different argument, however, than saying that addiction research is unnecessary, that human studies are all that is needed, or that the animals are abused. We in the scientific community wholeheartedly support ethical, humanely-conducted research on addiction to nicotine and other drugs of abuse, which is in the public’s interest. At the same time, we condemn this irresponsible and factually-challenged assault on research at the NCTR.

Conclusion

We, the undersigned, support the careful, considered and regulated use of primates in addiction research. While respecting Dr. Jane Goodall as an eminent primatologist—known for her knowledge of chimpanzee behavior in the wild—we do not believe she has the necessary expertise to intervene into the scientific questions of addiction research and neuroscience. Addiction is a major public health issue worldwide, and requires and deserves close scientific scrutiny, some of which will require the use of animals.

James K. Rowlett, Ph.D., Professor and Vice Chair for Research, Department of Psychiatry & Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Jack E. Henningfield, Ph.D., Vice President, Research, Health Policy, and Abuse Liability, Pinney Associates, Inc. and Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Marina Picciotto, Ph.D., Charles B.G. Murphy Professor of Psychiatry and Professor in the Child Study Center, of Neuroscience and of Pharmacology, Deputy Chair for Basic Science Research, Dept. of Psychiatry, Deputy Director, Kavli Institute for Neuroscience, Yale University

Travis Thompson, Ph.D., L.P., Professor, University of Minnesota; Past President of American Psychological Association Division of Psychopharmacology and Substance Abuse; Past Member, College on Problems of Drug Dependence Executive Committee

Charles P. France, Ph.D., Robert A. Welch Distinguished University Chair in Chemistry, Professor of Pharmacology and Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center- San Antonio

Michael A. Nader, Ph.D., Professor of Physiology, Pharmacology, and Radiology and Director, Center for the Neurobiology of Addiction Treatment; Co-Director, Center for Research on Substance Use and Addiction, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Thomas Eissenberg, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology (Health Program) and

Director, Center for the Study of Tobacco Products, Virginia Commonwealth University

Nancy A. Ator, Ph.D., Professor of Behavioral Biology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Roger D. Spealman, Ph.D., Professor of Psychobiology, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

Kathleen A. Grant, Ph.D., Chief and Senior Scientist, Division of Neuroscience, Professor, Dept. Behavioral Neuroscience, Oregon National Primate Research Center

Alan J. Budney, Ph.D., President, College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Past President, Division of Psychopharmacology and Substance Abuse (28) and the Division on Addictions (50) – American Psychological Association, Professor, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Peter W. Kalivas, Ph.D., Professor and Chair, Department of Neuroscience, Medical University of South Carolina

Marilyn E. Carroll, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota

Craig A. Stockmeier, Ph.D., Professor, Dept Psychiatry & Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Janet Neisewander, Ph.D., Professor, School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University

Mary E Cain, PhD, Professor of Psychological Sciences, Past President for Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology, Kansas State University

Wei-Dong Yao, PhD, Professor, SUNY Upstate Medical University

Lance R. McMahon, PhD, Chair and Professor of Pharmacodynamics, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida

Michael N. Lehman, Ph.D., Professor and Chair, Department of Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences, Chairman of the Board, UMMC Neuro Institute, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Donna M. Platt, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry & Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Michael A. Taffe, Ph.D., Associate Professor, The Scripps Research Institute

Linda J. Porrino, PhD, Professor and Chair, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Kevin B. Freeman, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry & Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Mei-Chuan Ko, Ph.D., Professor, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Sally L. Huskinson, Ph.D., Instructor, Department of Psychiatry & Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Mark Smith, PhD, Professor, Department of Psychology and Program in Neuroscience, Davidson College

Daniel C. Williams, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Director, Division of Psychology, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Eric J. Vallender, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Matthew Banks, PharmD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University

Paul May, Ph.D., Department of Neurobiology & Anatomical Sciences, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Juan Carlos Marvizon, Ph.D., Adjunct Professor, UCLA, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System

Catherine M. Davis, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Behavioral Biology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Klaus A. Miczek, Ph.D., Moses Hunt Professor of Psychology, Psychiatry, Pharmacology, & Neuroscience, Tufts University, Department of Psychology

Wendy J. Lynch, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, University of Virginia

Michael T. Bardo, Professor of Psychology, Director, Center for Drug Abuse Research Translation (CDART), University of Kentucky

Xiu Liu, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Pathology, Associate Director, Graduate Program in Pathology, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Katherine Serafine, PhD, Assistant Professor of Behavioral Neuroscience University of Texas at El Paso, Department of Psychology

Robert L. Balster, PhD, Butler Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Research Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry, former CoDirector of the Center for the Study of Tobacco Products, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

David Jentsch, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology, Binghamton University

William W. Stoops, Ph.D., Professor, University of Kentucky College of Medicine

Jack Bergman, Ph.D., McLean Hospital / Harvard Medical School

Barry Setlow, PhD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine

Doris J. Doudet, PhD, Professor, Dept. Medicine/Neurology, University of British Columbia

Leonard L. Howell, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University

S. Stevens Negus, PhD, Dept. of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University

Carrie K. Jones, Ph.D., Director, In Vivo and Translational Pharmacology, Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery, Vanderbilt University

Just wondering if ANY of you supposed learned people can explain something really simple to me. First, as of right now, the lab has been shut down. Second, I read that Jack Henningfield, among others (obviously) objected to this closure.

Someone, please, please explain to me how someone who graduated from college in 1974 and has spent the vast majority of their professional life studying nicotine and other harmful drug affects on primates need more time? It is 2018 people! That is 43 years of research.

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Katie Holleran, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow

Physiology and Pharmacology Department

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Anushree Karkhanis, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Physiology and Pharmacology

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Adding my nam in support of this letter:

Jeff L. Weiner, PhD

Professor, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Kimberly Raab-Graham, PhD

Associate Professor of Physiology and Pharmacology

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Sara R Jones, PhD

Professor

Department of Physiology and Pharmacology

Wake Forest School of Medicine

1/5/18 update:

https://speakingofresearch.com/2018/01/06/is-the-fda-is-undermining-its-own-study-and-the-experts-it-sent-to-review-it/

http://advocacy.apascience.org/blog/2018/1/5/american-psychological-association-science-alert-fda-shuts-down-nicotine-research-study-overlooking-concerns-of-scientific-organizations

Adding my name in support of this letter

John J. Curtin, PhD

Professor and Director of Clinical Training

Department of Psychology

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Richard De La Garza, II, Ph.D.

Professor

Baylor College of Medicine

Please add my name to the list of those in strong support of this letter:

Leonard Green, PhD

Professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences

Washington University in St. Louis

Adding my name in support of this letter:

James J. Mahoney, III, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor and Clinical Neuropsychologist

West Virginia University School of Medicine

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry

Jaye L. Derrick, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychology

University of Houston

I support this letter.

Cassandra D. Gipson, PhD

Assistant Professor of Psychology

Arizona State University

Megan Jo Moerke, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow

Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology

Virginia Commonwealth University

I’m adding my name in support of this letter.

Karen L. Hollis, Ph.D.,

Professor, Psychology & Education Department; and, Interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience & Behavior,

Mount Holyoke College

I support this letter, which provides the facts.

Mar Sanchez, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences

and Yerkes National Primate Research center

Emory University

I support this letter.

Blake Hilton, Psy.D.

Clinical Fellow in Psychology

Department of Psychiatry

McLean Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Joel W. Grube, Ph.D.

Senior Research Scientist

Prevention Research Center

PIRE

Adding my name in support:

Robert Leeman, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Health Education & Behavior

University of Florida

I support this letter.

Melissa Blank, PhD

Assistant Professor

Dept of Psychology

Behavioral Neuroscience

West Virginia University

Paul T. Harrell, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Division of Community Health and Research

Department of Pediatrics

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Adding my name in support.

Agree that “Importantly, it is unclear what evidence Goodall and White Coat Waste have for any serious violations of regulations at the FDA facility.” If there are violations, they should be investigated, but animal research can and does save lives.

I fully support the contents of this letter. Primate research is essential for understanding and developing treatments for many human diseases, including those that involve the nervous system, infection and the immune system, as well as reproductive and developmental processes.

Jon Hennebold Ph.D.

Professor & Chief, Reproductive & Developmental Sciences

Oregon National Primate Research Center

Oregon Health & Science University

Michele A. Basso, Ph.D.

Director, Fuster Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience

Professor, Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and Neurobiology

UCLA

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Jonah Sacha, PhD

Associate Professor

Oregon Health & Science University

I strongly agree with Clive Bates on this.

Whilst the direct effects of nicotine on the brain might be studied (and they’re already pretty well known) there is no correlation between the behaviours of primates and the behaviours of humans with respect to tobacco (reduced nicotine or not), nor any other addictive substance.

They simply cannot make the moral, social or commercial choices a human might (mail order, grey import, black market, duty free abuses etc) in order to gain access to a product, nor do they experience the political, social and moralistic pressures brought to bear on users of such products.

This is unjustifiable torture of another living creature.

I support and agree with the content of this letter.

Robert Lickliter, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

Florida International University

I absolutely support this letter.

Rueben Gonzales, Ph.D.

Professor of Pharmacology

The University of Texas at Austin

I strongly support this letter.

Rajeev I. Desai, PhD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry,

Harvard Medical School/Mclean Hospital

I am adding my name in support of this letter.

Carlton K. Erickson, PhD

Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology

The University of Texas at Austin

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Elizabeth T. Cox Lippard, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry

University of Texas at Austin

Tamara J. Phillips, Ph.D.

Professor of Behavioral Neuroscience

Director, Portland Alcohol Research Center

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland, OR 97239

Sarah Withey, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow

McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Christopher Cunningham, Ph.D., Department of Behavioral Neuroscience, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University

Adding my name to support this letter.

Andrey E Ryabinin, Ph.D.

Professor of Behavioral Neuroscience

Oregon Health & Science University

Adding my name in support of this letter

Ben Lovely, PhD

Post doctoral research fellow

University of Texas at Austin

I am surprised so many have signed onto this letter. Whatever you think of Goodall’s intervention, the more pressing concern is that these experiments serve no useful scientific purpose whatsoever. For what possible human behaviour does this primate research serve as a useful proxy? Certainly not smoking or vaping. Certainly not the response to ‘reduced nicotine cigarettes’ unless the monkeys could access a black market, buy from the internet, switch to hand-rolling tobacco or take up vaping. There needs to be a strong scientific justification for harming primates… what is it?

The justification is to keep the old gravy train rolling. With regard to smoking dependence or ‘nicotine dependence’ it has no relevancy at all, in 2017. With regard to maintaining salaries, it is everything.

You got it completely wrong: the research is not human behavior, which clearly would have to be done in humans. The research is not even on behavior. It is on the brain mechanisms that drive addiction. These research has been very successful, for example, in drawing the difference between craving, euphoria and withdrawal. It shows that while at the beginning drug consumption is driven by euphoria, later on craving takes its place while the pleasurable effects of the drug go down. As for withdrawal, understanding it is key to get the addict safely off the drug. All these is being investigated at the level of brain physiology, cell mechanisms and molecular pathways, not so much behavior.

John Crabbe, PhD

Professor, Behavioral Neuroscience

Oregon Health & Sciences University

R. Adron Harris, Ph.D. Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research, University of Texas at Austin.

Lisa M. Tarantino, PhD

Associate Professor of Genetics

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Bernard Le Foll, MD PhD

Medical Head, Addiction Medicine Service and Medical Withdrawal Service, Acute Care Program, CAMH.

Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine, Pharmacology, Psychiatry and Institute of Medical Sciences; University of Toronto.

I add my name in support of the letter.

Sara Jo Nixon, Ph.D.

Dept. of Psychiatry, University of Florida

Mary B. Zelinski, Ph.D.

Research Associate Professor

Division of Reproductive & Developmental Science

Oregon National Primate Research Center

Adding my full support to this letter.

Daniela Rüedi-Bettschen, PhD, Instructor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Marian L. Logrip, PhD

Assistant Professor

Addiction Neuroscience Graduate Program

Department of Psychology

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Alison Wakeford, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow

Department of Neuropharmacology and Neurologic Diseases

Yerkes National Primate Research Center

Emory University

I add my name in support of this letter:

Kenneth A. Perkins PhD, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Bethany Raiff, PhD

Associate Professor of Psychology

Rowan University

Stephen Boehm, PhD, Addiction Neuroscience Graduate Program, IUPUI

Add my name:

Richard G. Hunter, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychology

University of Massachusetts Boston

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Geary Smith, DVM, MS

Research Veterinarian

Department of Veterinary Resources

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute

Research with non-humans animals is critical for understanding how the brain works and how behavior alters brain function. It would be unethical to deny humans who suffer from addictive or other disorders the benefits of knowledge gained from controlled studies in non-humans.

Richard W. Foltin, Ph.D.

Professor, Columbia University Medical Center

NY, NY

Barbara J. Kaminski, Ph.D.

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Division of Behavioral Biology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Robert D. Hienz, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Behavioral Biology

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Graeme Mason

Gregg E. Homanics, PhD

Professor

Departments of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, and Neurobiology

University of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, PA 15261

Susan M. Brasser, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, San Diego State University

Below, I add my name in support of this letter:

Richard T. Born, MD

Professor of Neurobiology

Harvard Medical School

Julia A. Chester, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Psychological Sciences

Purdue University

703 Third Street

West Lafayette, IN 47907-2081

Meredith Halcomb, PhD

Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Indiana University School of Medicine

Gregory T. Collins, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

I fully support this letter. Please add my name as well.

Elise Weerts, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Behavioral Biology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Nicole M. Cameron

Peter F Weed, MPH, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow

Department of Pharmacology

University of Texas Health Science Center – San Antonio

James S. MacDonall, PhD

Professor Emeritus of Psychology

Fordham University

Bronx, NY 10458

Please add my name.

Louis S. Harris, PhD.

Harvey Hague Professor, Emeritus

Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology

Virginia Commonwealth University

Richmond, VA

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Mark G. LeSage, PhD

Senior Investigator and IACUC Chair

Department of Medicine

Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation

Adjunct Professor

Department of Medicine

University of Minnesota

Adding my name in support of this letter:

David A. Washburn, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience

Georgia State University

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Jennifer Higa-King, PhD

Associate Professor, Psychology

Honolulu Community College

Peter G. Roma, Ph.D.

Senior Scientist and Director, Behavioral Health & Performance Laboratory

NASA Johnson Space Center and

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Keith A. Trujillo, PhD

Professor, Psychology

Director, Office for Training, Research and Education in the Sciences

California State University San Marcos

Margaret P. Martinetti, PhD

Associate Professor of Psychology

The College of New Jersey

John P. Capitanio, Ph.D.

Research Psychologist

University of California, Davis

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Patricia M. Di Lorenzo, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

Binghamton University

Mark Prendergast, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

University of Kentucky

Adding my name in support of the letter:

August Holtyn, Ph.D.

Research Associate

Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

Johns Hopkins University

Adding my name in support of the letter

Ryan LaLumiere, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences

University of Iowa

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Chana Akins, PhD

Professor of Psychology

University of Kentucky

Dustin J. Stairs, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Creighton University, Department of Psychology

Adding my support to this letter:

Jeremy D. Bailoo, PhD

Excuse me? Tobacco user fees are surely borne by the taxpaying consumer and not the industry since the industry, in response to such fiscal assaults, inevitably raises the price of its products to cover it. For one, the Master Settlement Agreement is a testament to that. And it is not the only example. Trying to say that the tobacco user fee only comes out of the industry’s pockets is like trying to convince us that raising tobacco taxes only hurts the industry when it’s part of the anti-smoker manual that to raise tobacco taxes is to affect the consumer (and not the industry) by forcing reduction or elimination of purchase.

Well all tobacco companies’ money comes from the consumer (that’s their only source of income), so in that sense all costs (including costs of production, advertising, etc) are borne, ultimately, by the tax payer. But in terms of where the money is coming from – who is literally paying it – it is industry, not consumers. It is wrong for Goodall to imply the taxpayer is paying for this research, the industry is – the fact that they ultimately get their money from consumers is neither here no there.

It appears you conflate income with tax. The company sells a product and receives a profit for it and the expense (i.e. “production, advertising, etc.”) that comes with it. But government comes along and adds additional punitive taxes and “fees” (just another word for tax) beyond the traditional sales tax. It’s disingenuous to lump profit and tax together. The subject is the “tobacco user fee” that only makes the industry the middleman between the government and its hands in the taxpayer’s pocket. It is the consumer that is paying for that cost that wouldn’t exist but for the government imposing it. It’s not just a company doing normal business. In fact, I’ll put my neck out and even call it money laundering by the govt. The money gets “clean” as it’s strained through the industry is what I’m hearing.

So what? It is not all taxpayers who pay for it, just the people who smoke. And those same people are precisely the ones who benefit for research on the diseases they will eventually get because they smoke. It seems fair and square to me.

First of all, your “so what?” ignores one of this paper’s primary rebukes of Goodall’s assertions. The authors spend a whole section on “Outright wrong: the FDA nicotine research Goodall targets is not taxpayer funded.” Ergo you’ve just disproved (at least in part) this paper’s accusation against Goodall.

Second of all, your reduction of taxpaying smokers to a “they don’t count” status when it comes to caring how taxpayer money is used is contemptible. It implies that adults who choose to smoke are beneath human respect. Which speaks volumes about this engrossment with nicotine research. Like your statement, it’s malevolent in nature, not benevolent. It seeks to control that which it cannot abide. It refuses to concede or allow to even contemplate that smoking is simply enjoyable for the act itself and not the nicotine just like people will still drink coffee minus the “addictive” caffeine because it’s what else the coffee offers that they want.

But I slightly digress. You say the use of smokers’ money is all good because “those same people are precisely the ones who benefit for research on the diseases they will eventually get because they smoke.” No, what you’re saying is that it’s okay to transfer the wealth of adult taxpayers who smoke to non-smokers. Why? Because all human beings suffer from all diseases. Everyone benefits from research on diseases, regardless of the alleged cause. And, I’ll add, it’s hyperbole to make a blanket statement that all smokers “will eventually get.” More smokers than not do not “eventually” get sick. And today we hear how the number of lung cancer cases are booming among non-smokers. So, no, none of this is “all fair and square.”

I add my name in support of the contents of this letter.

I add my name in support. Karen G. Anderson, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Behavioral Pharmacology, West Virginia University.

Adding my name in support of this letter.

Nancy K. Dess, PhD

Professor of Psychology

Occidental College

David F. Werner, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychology, Binghamton University – SUNY

Brandon Oberlin, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Indiana University School of Medicine

Melissa Herman

Assistant Professor

Department of Pharmacology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Thank you, James and colleagues, for this important and well thought-out response. I agree wholeheartedly.

Paul W. Czoty, Associate Professor

Dept. of Physiology & Pharmacology

Wake Forest School of Medicine

Winston-Salem, NC 27157

I am all for science and research into making more effective treatments for addiction. I also stand with the idea that animal research contributes to strides in such research. However, I disagree with the mindset that addiction is a “disease” in the sense of taking away aspects of personal responsibility not found in other “diseases” and glossing over the pain addiction causes to others in society. There is plenty of evidence as to the biochemical processes of addiction in the brain, and that there are plenty of chemical changes, so once one becomes addicted, one cannot physically just have the “willpower” to stop without help. I don’t deny this as a major factor in addiction and believe it’s solely poor will power or “miasmas” and the like, but what sets addiction apart for other ailments is that one has to start it by making a poor choice such as drinking or drugs. People with heart disease didn’t bring it on themselves, although one could argue that choices in diet / exercise can play a role, it is a less direct role with more variables to consider. If someone decides to take a drug and gets addicted, that choice is much more connected to the outcome of addiction. Addiction is easily preventable: don’t drink and take drugs. People who choose to use such things should be responsible for the negative consequences without being portrayed as “victims”.

Science cannot make a moral judgement on addiction as it cannot make moral judgement on anything. Science can tell us the biochemistry of addiction, and give us conclusions such as addiction having a chemical basis in the brain. However, we can make our own judgments surrounding the conclusions we get from science even if a scientific investigation can’t quantify morality. The conclusions made from research into the biochemistry of addiction can give us better treatment models, but they still do not diminish the personal responsibility involved in addiction. As a society, we should look at addiction with a more critical eye than it being compared to diseases in which one has little to no control over. Addicts are not passive “victims” of circumstances out of their control. They chose to make bad choices that affect society as a whole, by taking drugs or misusing alcohol. Scientifically, one may argue that the chemical changes in the brain make it “diseased”, but using the same “disease” model to view addiction the same way we view other diseases takes away that key aspect of personal responsibility that sets addiction apart. As they say, prevention is the best cure, and addiction one can argue, is 100% preventable by simply making a choice not to misuse whatever made them addicted in the first place. More research into rehabilitating addicts is great, but a more relaxed view of their accountability as to why they’re addicts in the first place isn’t.

Thank you for making a nuanced argument. Yes, there are people that decide to take drugs and get addicted as a consequence. However, there are other routes to addiction. For example, the main cause of the current opiate epidemic is chronic pain. Doctors started giving chronic pain patients Oxycontin, a new opiate that was marketed as non-addictive. Oxycontin then produced opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH): it decreased pain in the short term but increased it long-term. OIH has been know to basic scientists for decades, but the MDs are just not listening. Faced with increased chronic pain, the patient asks the doctor for more Oxycontin. At some point the doctor becomes concerned with the patient getting addicted and stops writing the prescription. Desperate, the patient turns to the black market, only to realize that heroin is cheaper than Oxycontin. He starts taking heroin and becomes addicted. One day he buys heroin that contains fentanyl, a hugely potent opiate, overdoses and dies. Many people are following that path.

When it comes to nicotine, the story is quite different. Cigarettes have been marketed for centuries and became part of the culture. People become addicted to nicotine as teenagers and then find it extremely hard to get off.

Addiction also has a strong genetic component. Some people become addicted to anything (even gaming and religion) while others are very resilient to addiction. We know all this largely because of basic research using animals.

Thanks for bringing that up. I understand that can happen, and probably those I believe are the most deserving of the benefits of such research. However, I still feel many misuse the “disease” model to try to decrease stigma, but it only creates a lack of accountability. I know this debate is quite heated in light of addiction touching many people personally, but it is refreshing to debate it on a more intellectual, than personal level, as much of this debate on social media is quite heated! I hope my comment (and yours!) gets people to think more about the implications of our new “disease” based model on society.

Stigma never cured or stopped anything. All it does is turn the oh-so-well-meaning stigmatizers into The Enemy. .

Cristine L. Czachowski, PhD, Addiction Neuroscience Graduate Program, IUPUI

Adding my name in support of this letter:

Ziva D Cooper, PhD

Associate Professor of Clinical Neurobiology (in Psychiatry)

Columbia University Medical Center